*********

Concerning the period of Baha’u’llah’s banishment to Iraq, specifically the time from March 12, 1852 through April 10, 1854

The cup of Bahá’u’lláh’s sorrows was now running over. All His exhortations, all His efforts to remedy a rapidly deteriorating situation, had remained fruitless. The velocity of His manifold woes was hourly and visibly increasing. Upon the sadness that filled His soul and the gravity of the situation confronting Him, His writings, revealed during that somber period, throw abundant light. In some of His prayers He poignantly confesses that “tribulation upon tribulation” had gathered about Him, that “adversaries with one consent” had fallen upon Him, that “wretchedness” had grievously touched Him, and that “woes at their blackest” had befallen Him. God Himself He calls upon as a Witness to His “sighs and lamentations,” His “powerlessness, poverty and destitution,” to the “injuries” He sustained, and the “abasement” He suffered. “So grievous hath been My weeping,” He, in one of these prayers, avows, “that I have been prevented from making mention of Thee and singing Thy praises.” “So loud hath been the voice of My lamentation,” He, in another passage, avers, “that every mother mourning for her child would be amazed, and would still her weeping and her grief.” “The wrongs which I suffer,” He, in His Lawḥ-i-Maryam, laments, “have blotted out the wrongs suffered by My First Name (the Báb) from the Tablet of creation.” “O Maryam!” He continues, “From the Land of Ṭá (Ṭihrán), after countless afflictions, We reached ‘Iráq, at the bidding of the Tyrant of Persia, where, after the fetters of Our foes, We were afflicted with the perfidy of Our friends. God knoweth what befell Me thereafter!” And again: “I have borne what no man, be he of the past or of the future, hath borne or will bear.” “Oceans of sadness,” He testifies in the Tablet of Qullu’ṭ-Ṭa‘ám, “have surged over Me, a drop of which no soul could bear to drink. Such is My grief that My soul hath well nigh departed from My body.” “Give ear, O Kamál!” He, in that same Tablet, depicting His plight, exclaims, “to the voice of this lowly, this forsaken ant, that hath hid itself in its hole, and whose desire is to depart from your midst, and vanish from your sight, by reason of that which the hands of men have wrought. God, verily, hath been witness between Me and His servants.” And again: “Woe is Me, woe is Me … All that I have seen from the day on which I first drank the pure milk from the breast of My mother until this moment hath been effaced from My memory, in consequence of that which the hands of the people have committed.” Furthermore, in His Qaṣídiy-i-Varqá’íyyih, an ode revealed during the days of His retirement to the mountains of Kurdistán, in praise of the Maiden personifying the Spirit of God recently descended upon Him, He thus gives vent to the agonies of His sorrow-laden heart: “Noah’s flood is but the measure of the tears I have shed, and Abraham’s fire an ebullition of My soul. Jacob’s grief is but a reflection of My sorrows, and Job’s afflictions a fraction of my calamity.” “Pour out patience upon Me, O My Lord!”—such is His supplication in one of His prayers, “and render Me victorious over the transgressors.” “In these days,” He, describing in the Kitáb-i-Íqán the virulence of the jealousy which, at that time, was beginning to bare its venomous fangs, has written, “such odors of jealousy are diffused, that … from the beginning of the foundation of the world … until the present day, such malice, envy and hate have in no wise appeared, nor will they ever be witnessed in the future.” “For two years or rather less,” He, likewise, in another Tablet, declares, “I shunned all else but God, and closed Mine eyes to all except Him, that haply the fire of hatred may die down and the heat of jealousy abate.”

Mírzá Áqá Ján himself has testified: “That Blessed Beauty evinced such sadness that the limbs of my body trembled.” He has, likewise, related, as reported by Nabíl in his narrative, that, shortly before Bahá’u’lláh’s retirement, he had on one occasion seen Him, between dawn and sunrise, suddenly come out from His house, His night-cap still on His head, showing such signs of perturbation that he was powerless to gaze into His face, and while walking, angrily remark: “These creatures are the same creatures who for three thousand years have worshipped idols, and bowed down before the Golden Calf. Now, too, they are fit for nothing better. What relation can there be between this people and Him Who is the Countenance of Glory? What ties can bind them to the One Who is the supreme embodiment of all that is lovable?” “I stood,” declared Mírzá Áqá Ján, “rooted to the spot, lifeless, dried up as a dead tree, ready to fall under the impact of the stunning power of His words. Finally, He said:‘Bid them recite:

“Is there any Remover of difficulties save God? Say: Praised be God! He is God! All are His servants, and all abide by His bidding!”

Tell them to repeat it five hundred times, nay, a thousand times, by day and by night, sleeping and waking, that haply the Countenance of Glory may be unveiled to their eyes, and tiers of light descend upon them.’ He Himself, I was subsequently informed, recited this same verse, His face betraying the utmost sadness.… Several times during those days, He was heard to remark: ‘We have, for a while, tarried amongst this people, and failed to discern the slightest response on their part.’ Oftentimes He alluded to His disappearance from our midst, yet none of us understood His meaning.”

Finally, discerning, as He Himself testifies in the Kitáb-i-Íqán, “the signs of impending events,” He decided that before they happened He would retire. “The one object of Our retirement,” He, in that same Book affirms, “was to avoid becoming a subject of discord among the faithful, a source of disturbance unto Our companions, the means of injury to any soul, or the cause of sorrow to any heart.” “Our withdrawal,” He, moreover, in that same passage emphatically asserts, “contemplated no return, and Our separation hoped for no reunion.”

Suddenly, and without informing any one even among the members of His own family, on the 12th of Rajab 1270 A.H. (April 10, 1854), He departed, accompanied by an attendant, a Muḥammadan named Abu’l-Qásim-i-Hamadání, to whom He gave a sum of money, instructing him to act as a merchant and use it for his own purposes. Shortly after, that servant was attacked by thieves and killed, and Bahá’u’lláh was left entirely alone in His wanderings through the wastes of Kurdistán, a region whose sturdy and warlike people were known for their age-long hostility to the Persians, whom they regarded as seceders from the Faith of Islám, and from whom they differed in their outlook, race and language.

Attired in the garb of a traveler, coarsely clad, taking with Him nothing but his kashkúl (alms-bowl) and a change of clothes, and assuming the name of Darvísh Muḥammad, Bahá’u’lláh retired to the wilderness, and lived for a time on a mountain named Sar-Galú, so far removed from human habitations that only twice a year, at seed sowing and harvest time, it was visited by the peasants of that region. Alone and undisturbed, He passed a considerable part of His retirement on the top of that mountain in a rude structure, made of stone, which served those peasants as a shelter against the extremities of the weather. At times His dwelling-place was a cave to which He refers in His Tablets addressed to the famous Shaykh ‘Abdu’r-Raḥmán and to Maryam, a kinswoman of His. “I roamed the wilderness of resignation” He thus depicts, in the Lawḥ-i-Maryam, the rigors of His austere solitude, “traveling in such wise that in My exile every eye wept sore over Me, and all created things shed tears of blood because of My anguish. The birds of the air were My companions and the beasts of the field My associates.” “From My eyes,” He, referring in the Kitáb-i-Íqán to those days, testifies, “there rained tears of anguish, and in My bleeding heart surged an ocean of agonizing pain. Many a night I had no food for sustenance, and many a day My body found no rest.… Alone I communed with My spirit, oblivious of the world and all that is therein.”

In the odes He revealed, whilst wrapped in His devotions during those days of utter seclusion, and in the prayers and soliloquies which, in verse and prose, both in Arabic and Persian, poured from His sorrow-laden soul, many of which He was wont to chant aloud to Himself, at dawn and during the watches of the night, He lauded the names and attributes of His Creator, extolled the glories and mysteries of His own Revelation, sang the praises of that Maiden that personified the Spirit of God within Him, dwelt on His loneliness and His past and future tribulations, expatiated upon the blindness of His generation, the perfidy of His friends and the perversity of His enemies, affirmed His determination to arise and, if needs be, offer up His life for the vindication of His Cause, stressed those essential pre-requisites which every seeker after Truth must possess, and recalled, in anticipation of the lot that was to be His, the tragedy of the Imám Ḥusayn in Karbilá, the plight of Muḥammad in Mecca, the sufferings of Jesus at the hands of the Jews, the trials of Moses inflicted by Pharaoh and his people and the ordeal of Joseph as He languished in a pit by reason of the treachery of His brothers. These initial and impassioned outpourings of a Soul struggling to unburden itself, in the solitude of a self-imposed exile (many of them, alas lost to posterity) are, with the Tablet of Kullu’ṭ-Ṭa‘ám and the poem entitled Rashḥ-i-‘Amá, revealed in Ṭihrán, the first fruits of His Divine Pen. They are the forerunners of those immortal works—the Kitáb-i-Íqán, the Hidden Words and the Seven Valleys—which in the years preceding His Declaration in Baghdád, were to enrich so vastly the steadily swelling volume of His writings, and which paved the way for a further flowering of His prophetic genius in His epoch-making Proclamation to the world, couched in the form of mighty Epistles to the kings and rulers of mankind, and finally for the last fruition of His Mission in the Laws and Ordinances of His Dispensation formulated during His confinement in the Most Great Prison of ‘Akká.

Shoghi Effendi-God Passes By-Baha’u’llah’s Banishment to Iraq

*********

*********

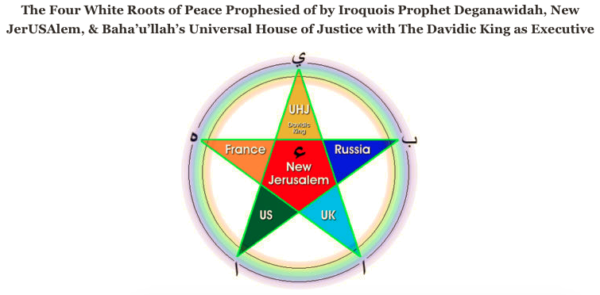

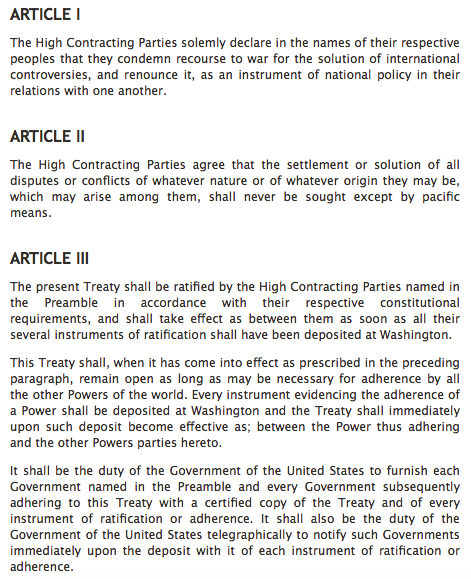

Articles of General Treaty #2137 binding all of the nations that are signatories thereto and all of the inhabitants thereof to the Everlasting Covenant of LOVE!